Introduction

The PAB project has been working on the evidence of fire use by early humans, with a focus on three sites in the Breckland of Suffolk – at Barnham, Beeches Pit and Devereux’s Pit. Here we provide summaries of the research at each of the sites, and the recently published research from Barnham of the earliest evidence of making fire.

Go straight to:

Earliest evidence of making fire at Barnham

Background

Determining when humans first controlled fire is a critical area of research for understanding human biological, technological and social evolution. Human fire use probably began over 1.5 million years ago with the use of wildfires, progressing to deliberate gathering of embers and feeding the fire. The earliest evidence is often equivocal, consisting of heated stone tools from sites in Kenya, dating to 1.6-1.4 million years ago, and South Africa at 1.0-0.8 million years ago. But using wildfire was difficult, being dependent on lightning strikes, and costs of maintaining the fire. The ability to make fire dealt with these challenges.

In Europe there is occasional evidence of fire-use from around 400,000 years ago, the main sites being Menez-Dregan and Terra Amata in France, Gruta da Aroeira in Portugal and in the UK at Beeches Pit, just 10 km south-west of Barnham. Until now, evidence of making fire has been limited to several French late Neanderthal sites dating to c.50,000 years ago, which have handaxes showing impact marks from iron pyrite to create sparks for making fire. But at Barnham we have evidence that fire-making occurred considerably earlier at over 400,000 years ago by early Neanderthals.

Barnham

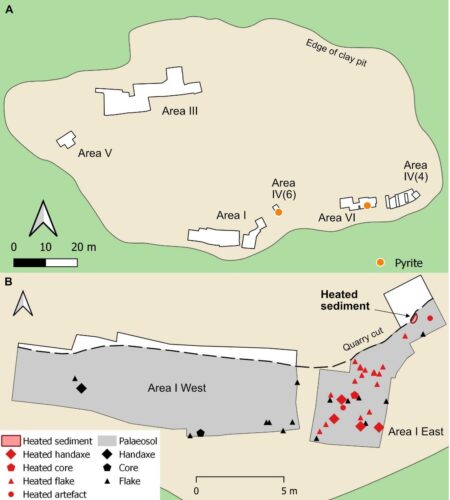

The Barnham site lies within a disused clay pit in the Breckland of Suffolk. Following previous work in the early 20th century, more extensive excavations were undertaken in 1989-1994 and currently since 2013. The deposits occupy a small basin, formed within a glacial channel cut into Chalk bedrock, c. 450,000 years ago, and overlain by interglacial pond sediments, laid down during the first part of Hoxnian interglacial, c. 400,000 years ago. In the middle of the basin the pond sediments reach a depth of 5 m and contain rich fauna and flora. The pond sediments thin out towards the southern edge of the pond, being a mere 30 cm deep, and lie above a coarse flint gravel, which formed a source of raw material for two early human groups. The first group knapped simple cores and flakes but were soon replaced by a different group who made handaxes. The second group arrived as the pond was drying out, and as an ancient soil developed across the site.

Evidence of fire-use

The evidence of fire is associated with the second human group, and consists of fire-cracked flint, heat-shattered handaxes, occasional charcoal, but importantly a discovery in 2021 of a patch of baked sediment in Area I East. The baked sediment is a reddened clay that lies within the ancient soil, being only 55 cm across and partially truncated by the quarry digging in the early 1900s. Proving that it was caused by human fire has taken four years of excavation and analysis. Much of the analytical work has been undertaken by Sally Hoare of the University of Liverpool using three techniques. The first – micromorphology – demonstrates that the reddening of the sediment was caused by heating, while study of the magnetic properties showed conversion of the iron minerals to haematite, suggesting repeated heating. A third study examined the light and heavy hydrocarbons, with the former associated with fast-burning wildfires, but the latter with more sustained fire-use by humans; the reddened sediment had a predominance of heavy hydrocarbons, suggesting that humans were responsible. Finally, Fourier-transform Infrared analysis by Marcus Hatch at Queen Mary University of London, shows that the reddened sediment reached temperatures of more than 700 °C.

All of these analyses strongly indicate that the patch of reddened clay was a campfire that had been repeatedly used. As further confirmation, excavation of the ancient soil around the campfire, contained fire-cracked flint, as well as four heat-shattered handaxes.

Pyrite – evidence of making fire

Evidence of actually making fire comes from two tiny pieces of iron pyrite that were also found in the ancient soil. Although the pieces are oxidised, the radial crystal structure of the fragments indicates pyrite, a natural mineral that in later periods was often used to strike against flint to create sparks for lighting fires.

As a naturally occurring mineral, the challenge has been to demonstrate that it was brought to Barnham by humans. Fortunately, a member of the team, Simon Lewis from Queen Mary University of London, has been undertaking geological research in the area for over 35 years. Part of the work has been identifying both the local rocks, and those brought into the area by glaciers or rivers. Over 121,000 rocks from 26 sites- including Barnham – have been identified, and not a single one is pyrite. In other words, pyrite is extremely rare in this part of Suffolk, and the only time it occurs is in association with a campfire and heat-shattered handaxes – the inescapable conclusion is that humans were making fire, 350,000 years earlier than previously thought.

Implications

The most compelling evidence for fire-making comes from the artefacts and campfire in Area I East, but other areas of the site also suggest regular use; in particular, concentrations of heated flint in Area VI, located 45 m to the east, so-called ‘ghost fires’. Of significance is other evidence of fire-use in this part of Suffolk around 400,000 years ago. At Beeches Pit, 10 km south-west of Barnham, at least three distinct burning horizons, including probable hearths and heated artefacts, have been identified. Similarly, at Devereux’s Pit just 500 m west of Beeches Pit and also dating to this period, excavations have revealed heated flint artefacts. Notably, all three sites occupy marginal locations, away from the main river valleys and associated with small ponds or springs. In the absence of caves, these locations likely provided safer, more sheltered environments for domestic activities. Taken together, these findings present a strong case for persistent, controlled fire use in East Anglia 400,000 years ago.

The ability to make fire had huge technological, biological and social implications. Other than protection and warmth, it allowed predictability, with better planning of seasonal routines and the establishment of domestic sites in preferred locations. It would have enabled routine cooking, which widened food resources by removing toxins from many roots and tubers, or pathogens from meat. By tenderising foods, it improved digestion, freeing up energy for development of the brain. Improved cognition would have enhanced communication and cooperation. Together with wider food resources, the ingredients were all in place for larger groups and more complex societies.

The evidence from Barnham strongly indicates complex behaviour, including an understanding of the properties of pyrite, knowledge of suitable tinder for successful ignition, and the curation of pyrite as part of a fire-making kit. This evidence sits alongside other markers of sophisticated human behaviour between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago, including bone and wood-working, improved hunting and skilled butchery. Collectively, these developments suggest a significant transition in human behaviour during this period, marked by a steady increase in brain size that approached modern levels. While these behavioural and cognitive changes certainly involved early Neanderthals in western Eurasia, it is likely that similar developments were occurring among the ancestors of Denisovans in eastern Eurasia and of Homo sapiens in Africa.

This is a brief summary of the paper published in Nature December 10th 2025:

Davis, R.J, Hatch, M., Hoare, S., Lewis, S.G., Lucas C., Parfitt, S.A., Bello, S.M., Lewis, M., Mansfield, J., Najorka,J., O’Connor, S., Peglar, S., Sorensen, A., Stringer, C.B., Ashton, N.M. (2025). Earliest evidence of making fire. Nature.

Devereux’s Pit

Introduction

Devereux’s Pit is a disused 19th Century clay pit located between the villages of Icklingham and West Stow in Suffolk, and approximately 500 m west of the internationally-renowned Lower Palaeolithic site at Beeches Pit. The site is recorded in the Geological Memoirs (1891), but, unlike Beeches Pit, it didn’t attract the attention of the scientific community until the end of the 20th Century. While working at Beeches Pit, a team led by David Bridgland, Simon Lewis and Richard Preece undertook some preliminary investigations at Devereux’s Pit during the 1990s. This involved cutting three sections into the former pit face, and drilling two boreholes. This work demonstrated three key characteristics of the site: 1) the presence of fine-grained Pleistocene sediments; 2) the preservation of faunal remains, with initial observations of species indicating deposition of the sediments under warm temperate climatic conditions; and 3) the presence of Lower Palaeolithic stone tools.

Further preliminary investigations were undertaken in 2017 and 2018 as part of the Breckland Palaeolithic Project. This work involved re-exposing one of the 1990s sections, excavating two test pits, and drilling a further three boreholes. This work demonstrated the presence of an archaeological horizon consisting of Acheulean stone tool technology with occasional fire-cracked flints in undisturbed Pleistocene silts.

2021-2023 Fieldwork

The first major phase of field investigations at the site got underway in the summer of 2021. Funded by the British Museum, this work consisted of a borehole survey and an archaeological excavation. Sediment cores provided information of the character, disposition and geometry of the geological deposits, enabling the depositional environment to be established. The cores were sampled to assess the preservation of faunal and floral remains. Initial species lists indicated deposition within a temperate fluvial environment. The preservation of opercula of Bithynia tentaculata permitted the use of amino acid geochronology to estimate the age of the site. Combined, this information indicated site formation during the Hoxnian interglacial (c. 400,000 years ago).

The excavation area was centred on the 2017 test pit that had identified an archaeological horizon in a grey silt. Much of this area had been affected by quarrying, so that blocks of intact sediment were isolated from each other by quarry pits. This area (Area I) was excavated over three seasons. The sediments in this area of the site are decalcified and therefore do not preserve faunal remains, but a rich stone tool record was recovered. Two assemblages were identified, representing two distinct stone tool industries. An assemblage consisting of cores, flakes and simple flake tools occurs in the lower part of the sequence, with flakes relating to handaxe manufacture identified in overlying sediments. These likely represent the Clactonian and Acheulean industries respectively, a succession of industries that has also been found at three other Hoxnian sites: Barnham, Swanscombe and Southfleet Road. This work will be the subject of a forthcoming publication.

2024-2025 excavation

Starting in 2024, a new excavation area (Area II) was established, centred on a borehole from which well-preserved animal bone had been encountered at a relatively accessible depth. The aim was to increase the size of the faunal assemblages to enable a more detailed reconstruction of the palaeoenvironment. Initially 2 x 2 m in extent, the excavation was expanded to 3 x 3 m during the 2025 season. A land surface with stone tools and degraded bone was encountered, providing a rare glimpse of early human behaviour.

Future Work

There is still much to be discovered at Devereux’s Pit. The work undertaken so far has established the depositional environment, the age of the site and the archaeological sequence. It has also identified the potential of the site for: 1) reconstructing Hoxnian environments and human habitat; 2) preservation of in situ archaeological material associated with faunal remains. Its potential importance is enhanced by the presence of three contemporary sites within 10 km at Barnham, Beeches Pit, and Elveden. Across these sites, there is evidence of human activity during the Hoxnian in a range of different geographical and environmental settings. For example, Devereux’s Pit provides evidence of human behaviour in a fluvial setting, whereas just 500 m to the east there is Beeches Pit with human activity around spring-fed ponds. Together, these sites have the potential to reveal much about the environmental context of different aspects of early human behaviour.

Beeches Pit

Introduction

Beeches Pit is a key site for understanding the development of fire-use during the Lower Palaeolithic. Archaeological excavations during the 1990s, led by John Gowlett of University of Liverpool, identified areas of burning in two separate layers, where patches of discoloured sediment had the appearance of having been baked by a campfire, and were associated with heated flints and Acheulean handaxe technology. Heated sediment had also been identified in a geological cutting, and burnt bone, charcoal and heated flints were found through much of the geological sequence at the site. In one area of burning, the stone tools appeared to be scattered around the discoloured sediments, suggesting fireside knapping. Furthermore, the heated sediments seemed to be overlapping, suggesting repeated use of this part of the site for campfires. This is exceptionally rare evidence of early fire-use for a site that is more than 400,000 years old.

Today, the site is a disused Victorian clay pit set within a forestry plantation. Surrounded by fast growing pine, the old pit itself is home to deciduous trees, including beech, in between which snake old trenches, with degraded cuttings and excavation areas cut in to the steep pit sides. Beeches Pit has long been known to the scientific community as a site of geological, palaeontological and archaeological interest since it was first described in the Memoirs of the Geological Survey in 1891. Excavations during the 1960s, led by Gale de G. Sieveking of the British Museum, resulted in the identification of another key characteristic of the site, a tuffaceous deposit that preserves a remarkably rich and diverse assemblage of land snails. First identified and described by Michael P. Kerney, this assemblage is known as the ‘Lyrodiscus fauna’ after its most notable species, Retinella (Lyrodiscus) elephantium. Although extinct, its cousin is now restricted to the Canary Islands. The Lyrodiscus fauna, which has also been identified at several other sites in Britain and France, lived during a period of warm, temperate climate just over 400,000 years ago, which, in Britain, is called the Hoxnian interglacial.

At the same time as the archaeological excavations, work at the site by Richard Preece and colleagues established the geological, faunal and environmental history of Beeches Pit. The sediments at the site preserve invertebrate and vertebrate remains that have enabled the reconstruction of the Hoxnian terrestrial environments. Some of these remains also have biostratigraphical significance that enable correlation of the Beeches Pit sequence to other Hoxnian sites. In particular, a change in the relative proportions of Discus ruderatus and Discus rotundatus has been identified at a number of Hoxnian sites, with the former associated with the early part of the interglacial (Bed 3b at Beeches Pit), and the latter becoming dominant in the late temperate phase of the Hoxnian (Bed 4 at Beeches Pit).

Recent work

Since 2013, sampling work and small-scale excavation has been undertaken as part of PAB and the Breckland Palaeolithic Project. This work has sought to understand the relationship between the archaeology and the environmental record. In particular, it has aimed to clarify the stratigraphic position of the main archaeological horizon in Area AH. This work was necessary due to a discrepancy between the stratigraphic scheme established during the geological investigations and how it was adapted in the archaeological excavations. The focus has been on establishing the molluscan record for the remaining sedimentary sequence in Area AH and relating it to the molluscan succession established from other areas of the site. The results have identified elements of the Lyrodiscus fauna in the Area AH sediments that also contain the Acheulean lithic assemblage and associated hearths. This places this evidence in Bed 4, which can be correlated with the late temperate phase of the Hoxnian interglacial.

A new study of the fire evidence has been undertaken by a multi-disciplinary team led by Sally Hoare at the University of Liverpool. This work has focussed on the patches of sediment that have previously been interpreted as hearths. Using a suite of modern analytical techniques, this work has established the nature of the fires that created them, and places human fire-use at the site in the context of the changing prevalence of wildfire in the wider landscape. This work is the subject of a forthcoming publication.

Future research

Beeches Pit remains a key site for understanding the major developments in human evolution around 400,000 years ago.

When did humans arrive at the site? Who were they and what technology did they use?

The sedimentary and environmental evidence shows that most of the Hoxnian is represented at the site, but at present we only have archaeological assemblages from the second half of the interglacial. A small number of flint artefacts have been found in sediments from the early part of the interglacial, so we know humans were there, but these have never been subjected to full archaeological excavation, which means we don’t have enough evidence to characterise the earliest human technology and behaviour at the site. Elsewhere, including at the neighbouring site at Devereux’s Pit, there are two different stone tool industries associated with humans during the Hoxnian. During the first half of the interglacial there was a relatively simple core and flake technology (the Clactonian Industry). Then, during the second half of the interglacial, assemblages with handaxes occur (Acheulean Industry). The evidence from Beeches Pit fits with the second part of this succession, but it remains to be seen whether the archaeology in the lower beds also conforms to this pattern.

Furthermore, the heated sediment from Bed 3b in Cutting 1 suggests humans were using fire at the site during the early temperate phase of the interglacial. Excavating more of Bed 3b will provide archaeological context to this fire evidence. For example, is it associated with Clactonian or Acheulean lithic technology?

What is the historical and environmental context of fire-use during the Hoxnian?

The fire evidence at Beeches Pit has the potential to provide both a historical and environmental perspective on fire-use during the Hoxnian, which is of renewed interest in light of the discovery 10 km to the northeast at Barnham of evidence for fire-making by a near-contemporary Acheulean population. At Beeches Pit, good evidence of fire-use occurs in three different beds associated with the early, late and post temperate phases of the Hoxnian. There is therefore an opportunity to study how fire was used as the environment changed over the course of the interglacial.

Further reading

Gowlett, J.A.J., Hallos, J., Hounsell, S., Brant, V. & Debenham, N.C. (2005). Beeches Pit—archaeology, assemblage dynamics and early fire history of a Middle Pleistocene site in East Anglia, UK. Journal of Eurasian Prehistory, 3, 3-40.

Hallos, J. (2005). “15 Minutes of Fame”: Exploring the temporal dimension of Middle Pleistocene lithic technology. Journal of Human Evolution, 49, 155-179.

Kerney, M.P. (1976). Mollusca from an interglacial tufa in East Anglia, with the description of a new species of Lyrodiscus Pilsbry (Gastropoda: Zonitidae). Journal of Conchology, 29, 47-50.

Preece, R.C., Gowlett, J.A.J., Parfitt, S.A., Bridgland, D.R., Lewis, S.G. (2006). Humans in the Hoxnian: habitat, context and fire use at Beeches Pit, West Stow, Suffolk, UK. Journal of Quaternary Science, 21, 485-496.

Preece, R.C., Parfitt, S.A., Bridgland, D.R., Lewis, S.G., Rowe, P.J., Atkinson, T.C., Candy, I., Debenham, N.C., Penkman, K.E.H., Rhodes, E.J., Schwenninger, J.-L., Griffiths, H.I., Whittaker, J.E. and Gleed-Owen, C. (2007). Terrestrial environments during MIS 11: evidence from the Palaeolithic site at West Stow, Suffolk, UK. Quaternary Science Reviews, 26, 1236–1300.