Rob Davis explains how excavations by the British Museum at Barnham, Suffolk, have uncovered evidence for arguably the most important innovation in human history, the ability to make fire.

Looking back through history and prehistory, it is clear how fundamental fire has been to the development of human civilisation. Great changes in human existence have had fire at the heart of them. The agricultural revolution required fire to turn crops into food, creating the surpluses that enabled the first towns, cities and monuments. The Copper Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, all dependant on fire to extract metal from ore and shape and combine it to make tools, weapons, jewellery and more. The industrial revolution and space age, powered by combustion. Fire is not just utilitarian, it is prominent in belief systems across the world, both extant and historically documented. Prometheus, Vesta’s flame, Shiva the divine cosmic dancer, the burning bush, Sacred Fire, the Holy Spirit, incense, funeral pyres; fire emblematic of and a conduit to the divine. We are a species that has harnessed and exploited the transformative power of fire, not just to survive and thrive on this planet, but also to make sense of the world around us.

The Barnham evidence

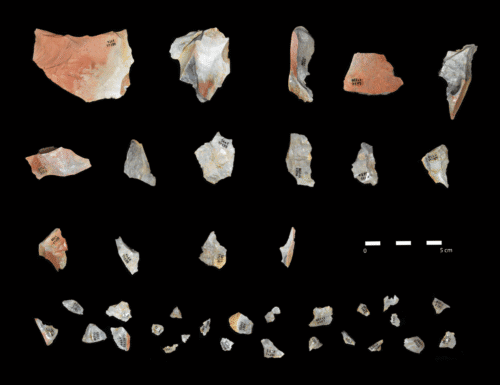

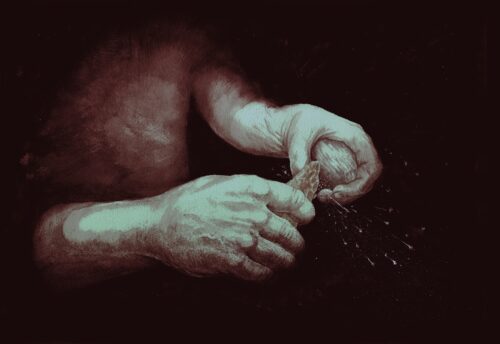

Since 2013, a team of archaeologists and scientists from the British Museum, Natural History Museum, Queen Mary University of London, UCL, University of Liverpool and Leiden University has been investigating the evidence for early fire-use at the Lower Palaeolithic site at Barnham, Suffolk. The evidence shows that the ability to create and control fire is not restricted to our own species, but a technology shared with other types of human that inhabited this world 400,000 years ago. Excavation of an ancient land surface has revealed an abundance of burnt materials associated with stone tools made and discarded by early Neanderthals. A patch of heated sediment, reddened like fired clay, is the remnants of a Neanderthal campfire. Adjacent to this is a cluster of artefacts, including fire-cracked handaxes, residues of fire-side activities. Most important of all, fragments of iron pyrite, brought to the site by Neanderthals for one purpose, to light fires by striking the pyrite with flint to create sparks. This is an extraordinary discovery, pushing back the earliest evidence for this technology by some 350,000 years.

Fire and early humans

Mastering fire is arguably one of the most important developments in human evolution. It seems likely that there is a very long history of human interaction with fire over more than a million years. It has been envisaged as a three stage process, beginning with foraging and scavenging in burnt landscapes following forest fires. The second stage involved the harvesting of wildfires, which were an occasional and unpredictable resource in the landscape. Embers collected in this way would have to be transported and then maintained, and once extinguished it became a waiting game for the next lightning strike. It is only with the third stage, the ability to create fire, that it could become a reliable addition to daily life. The knowledge of how to make fire enabled habitual use, which ultimately led to a reliance on fire for survival.

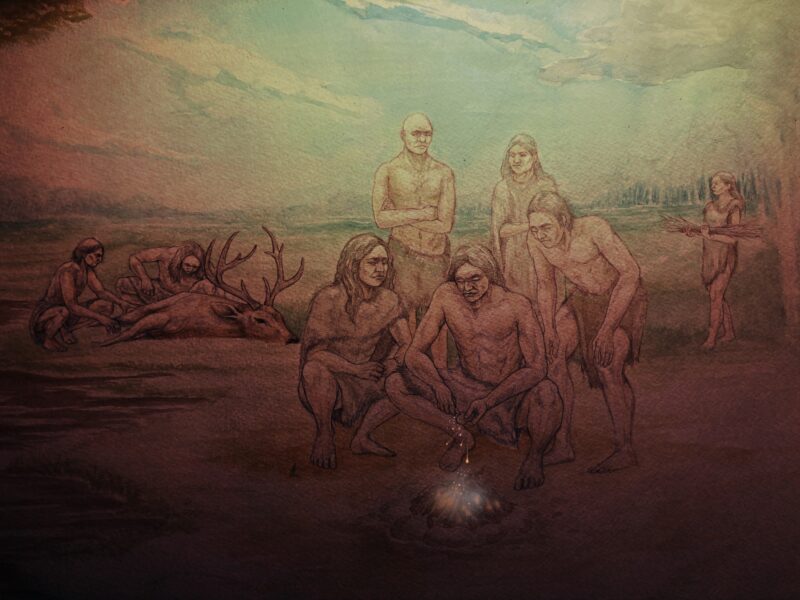

For early human hunter-gatherers, fire provided warmth and light and safety, a means to cook food to remove toxins and tenderise meat. It enabled humans to spread and thrive in colder, harsher environments, to explore subterranean spaces. Some of these benefits likely impacted biological and social evolution too. Cooking widened the range of available food sources and made food more readily digestible, which may have led to changes in the gut, but also freed up energy for development of the brain. Campfires acted as social hubs, focal points for interactions. Critically, fire extended the waking day by several hours. Humans live in complex social groups that require a significant daily time investment to maintain relationships. Socialising by firelight freed up daylight hours for hunting and gathering, collecting resources and making tools. It provided a setting for intense socialisation and development of language, storytelling and myth-making. With fire, humans could both feed and navigate larger, more complex societies.

The archaeology of early fire-use

There is still much we don’t know. To what extent is the evidence from Barnham representative of technological practises across the Palaeolithic world 400,000 years ago? Did other large-brained human species, such as the Denisovans in eastern Eurasia or early Homo sapiens in Africa, also light their own fires? And if so, did they invent fire-lighting technology independently, or adopt it through exchange of ideas and behaviours between human groups, or was it inherited from a common ancestor? How did the use of fire by early humans vary through time and space?

The problem is that fire-use rarely preserves well in the archaeological record and, prior to the development of hearth structures, it is notoriously hard to demonstrate. Ash and charcoal can easily be blown or washed away, and baked sediments can be eroded and dispersed. Heated artefacts survive but it is often difficult to rule-out incidental burning in a wildfire. Many of our early sites preserve evidence of activities related to resource collection, tool production or butchery, situations that wouldn’t have necessarily called for the immediate use of fire. Domestic sites located in sheltered parts of the landscape outside of major river valleys or coastal plains are potentially underrepresented in the archaeological record. The evidence is patchy, ambiguous and hard to interpret.

In light of these challenges, it is the preservation of the evidence at Barnham that is exceptional, whereas the technology itself may have been widespread 400,000 years ago. Indeed, there are other sites of similar age that also provide evidence of fire-use in the form of baked sediments, charcoal and associated heated artefacts and bones. Notable sites include Beeches Pit, located just 10 km to the southwest of Barnham in Suffolk, Menez-Dregan and Terra Amata in France, and Gruta da Aroeira in Portugal. Together, these sites point to an increase in the importance of fire to early humans between 500,000 and 400,000 years ago. Barnham provides an explanation, the advent of fire-making.

The transformative power of fire

Through time, humans would come to find ways to use fire to advance other technologies. The first archaeologically visible applications occur from 300,000 years ago. The rare survival of wooden artefacts at Schöningen, Germany, show the use of fire to harden spear tips. Tools begin to be hafted at this time, with evidence for the use of fire to produce birch bark tar for use as a glue for attaching stone blades and points to handles. At Qesem Cave, Israel, there is the earliest evidence for controlled heating of stone to improve its qualities for tool production. There was likely a multitude of other uses that do not leave an imprint on the archaeological record. Much later came ceramics and metals. Bit by bit, humans found new ways to utilise the power of fire to change the properties of materials and start to transform the world around them.

Many aspects of early human day-to-day life are alien to most of us in the modern world. Few people today have made tools from stone or wood, foraged for nuts, roots and tubers, or hunted animals with spears and butchered them with stone tools. We do know fire, though. Sitting round a campfire, listening to the chatter and laughter of our companions while staring at the flickering flames, it feels timeless, primeval. This is a profoundly human experience, which connects us across deep time to early human societies, be they Neanderthal or Homo sapiens or any other fire-using species, and in doing so it speaks to their unmistakable humanity.

Further Reading

Davis, R.J, Hatch, M., Hoare, S., Lewis, S.G., Lucas C., Parfitt, S.A., Bello, S.M., Lewis, M., Mansfield, J., Najorka,J., O’Connor, S., Peglar, S., Sorensen, A., Stringer, C.B., Ashton, N.M. (2025). Earliest evidence of making fire. Nature.

Project team

Nick Ashton, Silvia Bello, Rob Davis, Marcus Hatch, Sally Hoare, Mark Lewis, Simon Lewis, Claire Lucas, Jordan Mansfield, Jens Najorka, Simon O’Connor, Simon Parfitt, Sylvia Peglar, Andrew Sorensen and Chris Stringer

With thanks to…

Mareike Stahlschmidt, Christopher Jeans, Will Lord and Craig Williams

Duke of Grafton, Matthew Hawthorne, David Heading, Edward Heading, Richard Heading, David Switzer, Luke Dale, Xin Ding, Sophie Hunter, Dylan Jones, Izzy Klipsch, Murat Özturan, Aaron Rawlinson, Ian Taylor and Tudor Bryn Jones.

The research has been funded by the Calleva Foundation.